MPACT-Cheriot - A Fast and flexible simulator for the CHERIoT architecture

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has identified memory safety vulnerabilities as a major cybersecurity risk 1, pointing to reports that 70% or more of security vulnerabilities were found to involve memory-safety issues. CHERIoT 2 is a new architecture that seeks to provide strong protection against many frequently exploited memory vulnerabilities. CHERIoT is based on using CHERI 3 capability hardware-extensions to a 32 bit RISC-V 4 platform to provide fine-grained spatial and temporal safety, along with lightweight software compartmentalization. Standards like these are critical to broad adoption of security features 5, but companies implementing these also need a firm understanding of the performance tradeoffs of their implementations. In this article I introduce MPACT-Cheriot 6, an instruction-set simulator (ISS) that is designed to be extensible, easily modifiable, and fast, in order to enable rapid prototyping and debugging of the new architecture. MPACT-Cheriot is built on top of MPACT-RiscV 7, a RISC-V ISS built using the MPACT-Sim framework 8, all developed at Google and available on Github.

MPACT-Sim

MPACT-Sim is an ISS framework in C++ that was designed with the goal to improve the velocity of the simulator developer, to make it easy to create ISSs from scratch, and to rapidly and easily modify existing ISSs in response to ISA design changes or user-needed functional enhancements. In other words, MPACT-Sim enables rapid HW/SW co-design and early pre-Silicon software development.

Manually writing an instruction decoder is tedious and error prone. MPACT-Sim removes this task by providing tools that read in instruction descriptions and generate C++ code for instruction decoding and bit field extractions. This allows the developer to avoid writing thousands of lines of code and instead focus on instruction semantics and simulator functionality. The tools also generate code for instruction encoders to accelerate writing of assemblers, which is particularly useful in early stages of ISA development/extension, when regular codegen tools either do not exist for the architecture or have not been updated to use newly added instructions. It also avoids the need to be an expert in LLVM/GCC to iterate quickly on new instructions.

format Inst32Format[32] {

fields:

unsigned bits[25];

unsigned opcode[7];

};

format IType[32] : Inst32Format {

fields:

signed imm12[12];

unsigned rs1[5];

unsigned func3[3];

unsigned rd[5];

unsigned opcode[7];

overlays:

unsigned u_imm12[12] = imm12;

unsigned i_uimm5[5] = rs1;

};

instruction group RiscVGInst32[32] : Inst32Format {

addi : IType : func3 == 0b000, opcode == 0b001'0011;

};

Figure 1. Encoding specification for RISC-V addi instruction.

The instruction descriptions are divided into two pieces, each containing multiple pieces of information about each instruction. The first piece focuses on the encoding, describing the instructions’ encoding formats, the size, and detailed encoding, as seen in Figure 1. This description also allows for the description of overlays, which allows bitfields to be reinterpreted as different types, broken up, and concatenated (including with constants) to create new virtual bitfields. One use for this is to describe the RISC-V/CHERIoT instructions whose immediate fields are non-contiguous.

addi{: rs1, %reloc(I_imm12) : rd},

resources: {next_pc, rs1 : rd},

disasm: "addi", "%rd, %rs1, %I_imm12",

semfunc: "&RV64::RiscVIAdd";

Figure 2. Instruction specification for RISC-V addi instruction

The second piece of the descriptions (seen in Figure 2.) specify the

instructions’ operands, their resource usage (optional), disassembly format,

and binding to the C++ callables that implement the instructions’ semantics in

the simulator. The operands are enumerated in three sections delimited by

colons: a predicate operand (if any), a list of source operands, and a list of

destination operands. In Figure 2, the addi instruction is shown as having

source operands rs1 and I_imm12, and destination operand rd. The

%reloc() decorator is used to indicate an operand that may require a

relocation entry, but is only used if an assembler is generated (see below).

Additionally, the destination operand can also be annotated with a latency that

can be used together with resource modeling to simulate the effect of non-unit

instruction latencies.

Next, you can optionally define resources that an instruction reads and writes to make it easier to implement different instruction “issue” strategies that allow you to take into account the dependencies and the latencies between instructions.

A disassembly formatting string can be specified. This is used to create a representation of each decoded instruction, making it easy to create disassemblers and human readable traces of instructions, as well as allowing instructions to be printed in a command-line debug interface.

Lastly, the description includes a binding to the C++ callable in the simulator source that will be used to implement the instruction’s semantics and called every time the instruction is executed.

Loops present an opportunity to improve simulation speed. Therefore, when an instruction is decoded, the information about the instruction is stored in an instruction descriptor. This descriptor is stored in an internal instruction cache that eliminates the need to re-decode previously executed instructions, i.e., instructions from previous iterations of a loop. The cached instruction descriptors are invalidated individually, by range, or as a whole in response to updates of the instruction memory that could modify instruction words. This supports using software breakpoint instructions, overlays, run-time code-generation, and self-modifying code.

|

|---|

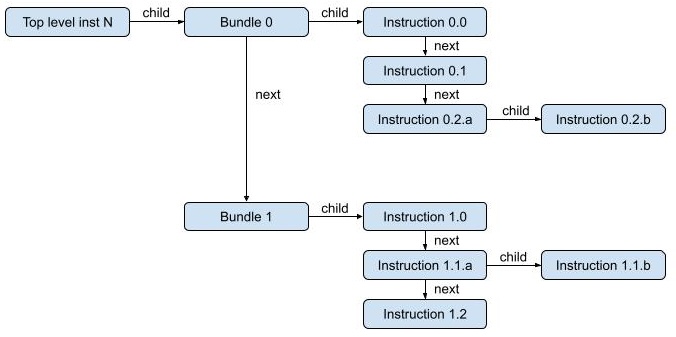

| Figure 3. Possible instruction-descriptor hierarchy tree for a VLIW instruction with two bundles, each consisting of 3 instructions, with two instructions broken into two phases. |

More advanced features allow instructions to be grouped in bundles (VLIW instruction words) and hierarchies of bundles, and for instruction semantics to be divided into multiple phases with separate instruction descriptors for each phase. An example of the latter allows the write-back of a load instruction to be executed separately (and asynchronously) from the address generation and memory request.

Each instruction semantic-function callable is invoked when the Execute()

method of an instruction-descriptor object is called. The semantic-function

callable takes a pointer to an instruction descriptor as its parameter. The

instruction descriptor contains vectors of pointers to access the interfaces of

the instruction operands. These interfaces are used to avoid having to

differentiate between accessing different operand types, such as literals,

immediate values, and register values. This allows the same semantic function

to be used for multiple instructions if they differ only in the type of their

operands, e.g., add register and add immediate.

MPACT-Sim provides classes to support modeling a large set of different architecture state objects. There are templated classes for use in modeling registers with different value types, as well as modeling scalar registers, vector registers, and array registers. The methods in the operand-access interfaces support accessing values from any of these objects.

// Generic helper function for binary instructions.

template <typename Register, typename Result, typename Argument>

inline void RiscVBinaryOp(const Instruction *instruction,

std::function<Result(Argument, Argument)> operation) {

using RegValue = typename Register::ValueType;

Argument lhs = generic::GetInstructionSource<Argument>(instruction, 0);

Argument rhs = generic::GetInstructionSource<Argument>(instruction, 1);

Result dest_value = operation(lhs, rhs);

auto *reg = static_cast<generic::RegisterDestinationOperand<RegValue> *>(

instruction->Destination(0))->GetRegister();

reg->data_buffer()->template Set<Result>(0, dest_value);

}

// Instruction semantic function for 'add' and 'addi'.

void RiscVIAdd(const Instruction *instruction) {

RiscVBinaryOp<RegisterType, UIntReg, UIntReg>(

instruction, [](UIntReg a, UIntReg b) { return a + b; });

}

Figure 4. The semantic function used for RISC-V add and addi instructions.

Unlike many other simulators and infrastructures, registers in MPACT-Sim are named and not numbered. That is, a register is identified by its name, not an index into a register-file structure implied by the instruction opcode (e.g., integer vs floating point). All registers derive from a common base class, and a map container is used to map from the name to the register object. The register name is generated by the decoder, which then uses it to look up the register object. This provides an abstraction from the register architecture of the target CPU and makes it easier to perform experiments with changing the number and organization of registers without impacting the simulator outside of the decoder.

Instruction semantic-functions access source and destination operands through abstract interfaces. The source-operand interface is shown below in Figure 5.

The interface is implemented by different operand-access objects customized to each underlying object. For instance, there is a register-access operand class as well as one for immediate values. This indirect method of accessing register operands does add some run-time overhead, but provides a great deal of flexibility. Instruction semantic functions are agnostic not only about the specific registers they work on, but also on whether the operand is a register or an immediate value. This indirection avoids coupling between the instruction semantics, operand types, and register architecture, allowing one to make significant changes in the register architecture and operands without modifying the instruction semantic functions.

// The source operand interface provides an interface to access input values

// to instructions in a way that is agnostic about the underlying implementation

// of those values (eg., register, fifo, immediate, predicate, etc).

class SourceOperandInterface {

public:

// Methods for accessing the nth value element.

virtual bool AsBool(int index) = 0;

virtual int8_t AsInt8(int index) = 0;

virtual uint8_t AsUint8(int index) = 0;

virtual int16_t AsInt16(int index) = 0;

virtual uint16_t AsUint16(int) = 0;

virtual int32_t AsInt32(int index) = 0;

virtual uint32_t AsUint32(int index) = 0;

virtual int64_t AsInt64(int index) = 0;

virtual uint64_t AsUint64(int index) = 0;

// Return a pointer to the object instance that implements the state in

// question (or nullptr if no such object "makes sense"). This is used if

// the object requires additional manipulation - such as a fifo that needs

// to be popped. If no such manipulation is required, nullptr should be

// returned.

virtual std::any GetObject() const = 0;

// Return the shape of the operand (the number of elements in each dimension).

// For instance {1} indicates a scalar quantity, whereas {128} indicates an

// 128 element vector quantity.

virtual std::vector<int> shape() const = 0;

// Return a string representation of the operand suitable for display in

// disassembly.

virtual std::string AsString() const = 0;

virtual ~SourceOperandInterface() = default;

};

Figure 5. Source-operand access interface used in instruction semantic functions.

MPACT-Cheriot

MPACT-Cheriot provides an ISS for the CHERIoT architecture using the MPACT-Sim infrastructure, similar to and based on the RISC-V simulators provided in MPACT-RiscV. It reuses many of the instruction semantic functions and instruction descriptions of the RISC-V 32 bit instruction set, and adds or modifies instruction descriptions for the CHERIoT instructions that access and manipulate capabilities.

The implementation issues a single instruction per cycle, and that instruction completes in the same cycle, so there are no dependencies to model. The instruction execution is performed inside a top-level class that implements an extension of the generic MPACT-Sim core debug-interface, allowing robust debug capability to be built on top of that class.

When invoked in interactive mode, the ISS is controlled from the debug

command-line interface (CLI) which uses the top-level class to provide a range

of debug commands. The ISS prompt provides the disassembly of the instruction to

be executed next, the current symbol, and additional information, such as if an

interrupt/exception was just taken or returned from. The ISS can be run,

stepped, and halted from the CLI. Registers and memory can be read and written.

Breakpoints and data watchpoints can be set and cleared. Breakpoints can be set

not only on individual instructions, but also on a change in control flow, a

taken interrupt (Figure 6) and/or exception (Figure 7) and its return. The ISS

detects if an interrupt or exception will immediately cause another and

immediately halts, for instance, if the first instruction in the handler would

cause an exception. The main set of registers, as well as the current

interrupt/exception stack can be shown using the the reg $all command as seen

in Figure 8.

[0] > break $interrupt

[0] > run

Stopped at taken interrupt 8000252c

cspecialrw csp, mtdc, csp

interrupt Machine timer interrupt

[0] >

Figure 6. Example showing break on interrupt.

[0] > break $exception

[0] > run

Crash recovery (inner compartment) test: Store silently ignored

Crash recovery (main runner) test: Calling crashy compartment returned (crashes: 0)

Crash recovery (main runner) test: Returning normally from crash test

Crash recovery (main runner) test: Calling crashy compartment to double fault and unwind

Crash recovery (inner compartment) test: Trying to fault and double fault in the error handler Stopped at exception 8000252c

cspecialrw csp, mtdc, csp exception

Exception taken at 8000e024: CHERI exception: bounds violation c8

[0] >

Figure 7. Example showing break on exception.

[0] > reg $all

Interrupt stack:

[0] exception Exception taken at 80002ec0: Environment call from M-mode

czero = 0x00000000 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

cra = 0x80002eaa (v: 1 0x800028a0-0x080003960 l: 0x0000010c0 o: 0x4 p: G R-cmg- X- ---)

csp = 0x80001180 (v: 1 0x80000ad0-0x0800011d0 l: 0x000000700 o: 0x0 p: - RWcmgl -- ---)

cgp = 0x8001beb0 (v: 1 0x8001bd60-0x08001c000 l: 0x0000002a0 o: 0x0 p: G RWcmg- -- ---)

ctp = 0x00000000 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

ct0 = 0x8001bd98 (v: 1 0x8001bd80-0x08001be70 l: 0x0000000f0 o: 0x0 p: G RWcmg- -- ---)

ct1 = 0x00000000 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

ct2 = 0x800066c0 (v: 1 0x800066a8-0x080006d00 l: 0x000000658 o: 0x1 p: G R-cmg- X- ---)

cs0 = 0x00000001 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

cs1 = 0x8001bd80 (v: 1 0x8001bd80-0x08001be70 l: 0x0000000f0 o: 0x0 p: G RWcmg- -- ---)

ca0 = 0x8001bf90 (v: 1 0x8001bd60-0x08001c000 l: 0x0000002a0 o: 0x0 p: G RWcmg- -- ---)

ca1 = 0x80001240 (v: 1 0x80001240-0x080001248 l: 0x000000008 o: 0x0 p: - RWcmgl -- ---)

ca2 = 0x00000000 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

ca3 = 0x00000000 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

ca4 = 0x00000001 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

ca5 = 0x00000000 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

pcc = 0x80002494 (v: 1 0x80002320-0x0800028a0 l: 0x000000580 o: 0x0 p: G R-cmg- Xa ---)

mepcc = 0x80002ec0 (v: 1 0x800028a0-0x080003960 l: 0x0000010c0 o: 0x0 p: G R-cmg- X- ---)

mtcc = 0x80002494 (v: 1 0x80002320-0x0800028a0 l: 0x000000580 o: 0x0 p: G R-cmg- Xa ---)

mtdc = 0x80000230 (v: 1 0x80000230-0x0800003c8 l: 0x000000198 o: 0x0 p: G RWcmgl -- ---)

mscratchc = 0x00000000 (v: 0 0x00000000-0x000000000 l: 0x000000000 o: 0x0 p: - ------ -- ---)

Figure 8. Example showing the result of a reg $all CLI command.

The ISS keeps track of the branch history, which can be printed on demand (Figure 9), listing the last N branch instructions and their destinations. The branch history includes interrupts/exceptions and their returns, and summarizes repeated branches (in a loop) by providing a branch count. The number of branches captured in the branch trace can be changed in the CLI.

[0] > branch-trace

From To Count

0x800037e2 -> 0x800037f6 1

0x80003804 -> 0x80002e54 1

0x80002e68 -> 0x8000384c 1

0x80003886 -> 0x800066c0 1

0x80006722 -> 0x80003888 1

0x8000388e -> 0x80003892 1

0x8000389e -> 0x80002e6c 1

0x80002e6e -> 0x80002e7c 1

0x80002e82 -> 0x80003706 1

0x80003716 -> 0x80002e86 1

0x80002e96 -> 0x80002e9e 1

0x80002ea6 -> 0x800038a0 1

0x800038ac -> 0x800038f6 1

0x80003902 -> 0x80003912 1

0x80003916 -> 0x80002eaa 1

0x80002ec0 -> 0x80002494 1

80002494 cspecialrw csp, mtdc, csp

[0] >

Figure 9. Example showing branch history.

The MPACT-Cheriot ISS is instrumented with a number of counters, the most important of which are for cycles and the number of instructions executed (which, when IPC=1, are always equal), but also a counter for every opcode in the ISA. The ISS supports cache modeling with configurable level-1 caches. These have counters for all the basic cache statistics. All counters are exported to a text protobuf 9 file at the end of simulation.

Instruction- and data-memory profiling are supported. The instruction profiler counts the number of times each instruction located in an executable region specified in the ELF input file is executed. The data profiler tracks which words in the address space have been accessed, but in the interest of space (a single bit vs. a 32 bit counter per word), does not track the access count or type.

There are two ISS versions provided. One is a standalone CHERIoT simulator, the other is a dynamic library that implements an interface that allows it to be imported, instantiated, and used as a CPU in Renode 10 system simulations. Renode is a development environment that allows you to run full unmodified software on a model of a full system. Applications running on systems are often distributed across a number of processors, whether on a single SoC or across chip boundaries, and access a number of peripherals and memories across the system. Being able to develop, run, and debug the full software pre-silicon on a simulated platform brings with it the same benefits as developing software for a single core using an ISS in terms of visibility, debuggability, and fan-out.

Renode provides debugging facilities and visibility at the system level and supports running a GDB server, but of course, only for processors already supported by GDB. For new architectures, or newly modified architectures, GDB support is often not available. The dynamic-library version of MPACT-Cheriot avoids having to enable GDB support by exposing the debug CLI interface on a TCP port, to which one can connect with telnet or a similar utility, to control the ISS just like the standalone version.

In addition to modeling the CHERIoT CPU, the MPACT-Cheriot ISS contains models for tagged and untagged RAM memories and memory-request routers, which are accessed using MPACT-Sim defined interfaces (though, in general, this is up to the implementor, as these interfaces are not mandatory, but there for convenience). The RISC-V CLINT 11 (core-local interruptor) is modeled by default (the base address is configurable). A model for the PLIC 12 (platform-level interrupt controller) is available, but is not modeled by default. In the standalone version, a simple UART (output only) is added (configurable base address) to allow UART-based “printing”.

Both simulator versions support semihosting. Semihosting allows the program running on the simulator to interact with the host system through traps that the simulator intercepts. Examples include functions that are normally provided by an operating system such as host system file I/O - including standard input, standard output, and standard error. The semihosting follows the RISC-V standard 13, which in turn is based on the ARM Semihosting Specification 14. A semihosting call is made when the following instruction sequence is encountered:

slli x0, x0, 0x1f

ebreak

srai x0, x0, 7

Upon executing the ebreak of the semihosting call, the simulator first

verifies that the neighboring instructions (which are effectively no-ops)

conform with a semihosting call. It then examines the contents of the a0 and

a1 registers, which contain the semihosting-call function id and the address

of the semihosting-call parameter block, respectively. It then performs the

requested function before resuming execution of the simulated program.

The MPACT-Cheriot ISS has also been adapted to work with TestRIG 15, a framework for testing RISC-V processors with random instruction generation. TestRIG works by feeding instruction-trace streams to multiple RISC-V implementations and comparing the result streams (encoded in a standardized trace format) from each of the targets. This allows for easier verification of MPACT-Cheriot against golden models, such as Sail 16.

In terms of performance, MPACT-Cheriot is comparatively fast at about 14 million simulated instructions per second when executing the CHERIoT RTOS test-suite 17 on a reasonably fast host. This is good performance for a simulator that doesn’t perform runtime code-generation. Moreover, this is about 48x faster than the Sail simulator for CHERIoT for the same program and host.

In summary, MPACT-Cheriot is an open-sourced, fast simulator that has excellent debug features to support early software development for the new CHERIoT architecture. It is based on the MPACT-Sim framework which made it easy to develop and modify to track ISA changes as they occurred. It can be used both standalone and as part of a Renode full-system simulation. Its speed and debug features have proven invaluable internally: “What was taking hours to debug now takes minutes!”.

References:

-

Bob Lord, “The Urgent Need for Memory Safety in Software Products”, CISA blog, December 2023. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/urgent-need-memory-safety-software-products. ↩

-

Amar, Saar, et al. “CHERIoT: Complete Memory Safety for Embedded Devices.” Proceedings of the 56th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, 2023. ↩

-

Watson, Robert N. M., et al. “An Introduction to CHERI.” Technical Report, University of Cambridge, Computer Laboratory, no. 941, 2019, https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/techreports/UCAM-CL-TR-941.pdf ↩

-

RISC-V International, http://community.riscv.org. ↩

-

Robert N.M. Watson, et al. “It Is Time to Standardize Principles and Practices for Software Memory Safety”, Communications of the ACM, volume 68, issue 2, pages 40-45. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3708553 ↩

-

Jeremiassen, Tor. “MPACT-Cheriot.”, March 2024, https://github.com/google/mpact-cheriot. ↩

-

Jeremiassen, Tor. “MPACT-RiscV.”, March 2023, https://github.com/google/mpact-riscv. ↩

-

Jeremiassen, Tor. “MPACT-Sim - Retargetable Instruction Set Simulator Infrastructure.”, March 2023, https://github.com/google/mpact-sim. ↩

-

“Protocol Buffers - Google’s data interchange format”, https://github.com/protocolbuffers/protobuf. ↩

-

“Renode”, https://renode.io. ↩

-

“RISC-V Advanced Core Local Interruptor Specification”, https://github.com/riscv/riscv-aclint. ↩

-

“RISC-V Platform-Level Interrupt Controller Specification”, https://github.com/riscv/riscv-plic-spec/blob/master/riscv-plic.adoc. ↩

-

“RISC-V Semihosting”, https://github.com/riscv-non-isa/riscv-semihosting. ↩

-

“Semihosting.” RealView Compilation Tools Developer Guide Version 4.0, ARM Ltd, Chapter 8, https://developer.arm.com/documentation/dui0203/j. ↩

-

Joannou, Alexandre, et al. “Randomized Testing of RISC-V CPUs using Direct Instruction Injection.” IEEE Design and Test, 2023, https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/347706/Randomized_Testing_of_RISC-V_CPUs_using_Direct_Instruction_Injection.pdf. ↩

-

Gray, K. E., Sewell, P., Pulte, C., Flur, S., & Norton-Wright, R. (2017). The Sail instruction-set semantics specification language (pp. 1-25). Technical report, Cambridge University, 2017, https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~pes20/sail/manual.pdf. ↩

-

“CHERIoT RTOS”, https://github.com/CHERIoT-Platform/cheriot-rtos. ↩