CHERIoT: The last ten years

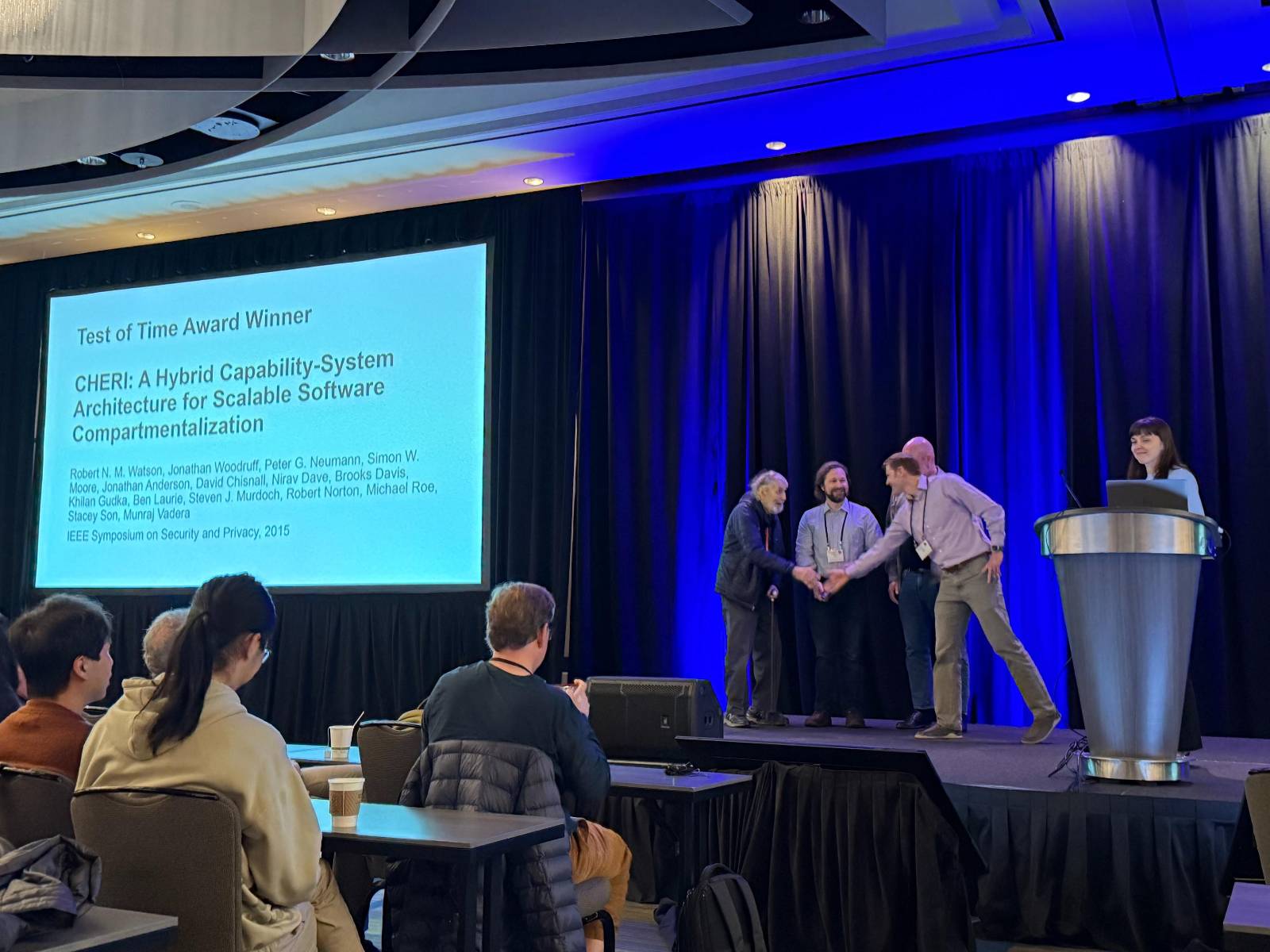

This week, we received an IEEE Security and Privacy Test of Time Award for the 2015 paper CHERI: A Hybrid Capability-System Architecture for Scalable Software Compartmentalization. This seemed like a good opportunity to look at how CHERI has changed from the time the paper was published to today’s CHERIoT (I’ll leave discussing other CHERI variants to some of the other coauthors - there’s a lot of ongoing CHERI work beyond this project!).

For those less familiar with the history, the CHERI project started in 2010 (I joined in 2012) with the DARPA CRASH programme asking ‘If you could change anything about computing to improve security, what would you do?’. CHERI built on experiences with Capsicum and historical capability systems to reimagine memory safety.

The CHERIoT project built on this prior work and started at Microsoft in 2019 when we began to think about scaling down some of the server-class ideas that we’d been working on for Azure to microcontrollers. We also asked what kind of system we could build if we could assume CHERI, and how can we simplify the hardware if we didn’t need other protection mechanisms. The CHERIoT ISA is tailored for a specific compartmentalisation model and core software stack, which is how we’re able to provide usable abstractions for compartmentalisation on such tiny hardware. A lot of other work on CHERI has focused more on big systems and incremental migration of truly huge software stacks such as the Chromium web browser running on a fully memory-safe kernel, display server, and so on.

Back in 2015, we thought 15 coauthors was a lot! The preceding 2014 paper had only nine coauthors, so I think this was the one where we discovered that the ACM LaTeX style had a hard-coded limit of 12 authors (and if you had that many, you ended up with an entire page listing the authors). The most recent CHERI technical report has 27 coauthors.

A lot is still the same

Looking back at the 2015 paper, it’s somewhat surprising how recognisable the system it describes would be for someone who is familiar with CHERIoT. A huge number of the features that make CHERIoT possible were there already. In particular, we’d already made two of the biggest changes from the first version of CHERI that I had used.

In the very first CHERI version, capability bounds were represented by a base and a top, but there was no separate address. In C, pointer arithmetic would move the base (truncating the capability) so you often needed to carry a separate offset. Around 2014, we changed this so the capability stored an offset instead. Microarchitecturally, this was actually an address, but we exposed it in the ISA as an offset from the base.

Exposing this address as an offset was my idea. I hoped that we would be able to create a C dialect where copying garbage collectors were possible. Any conversion from a pointer to an integer gave the offset unless you intentionally asked for the address (in which case it was your responsibility to ensure that you didn’t rely on that address being stable across GC sweeps). This meant that (in theory) you could relocate any object and update all capabilities to it (and, remember, the tag bit means that you can find all capabilities). I had a student, Munraj Vadera, write a copying GC for C and it worked! It could even do sub-object collection, so if you allocated an array and kept a bounded capability to a single element, the rest of the array could be collected.

I was very happy with this model. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a terrible idea. When Alex Richardson and Jessica Clarke tried to build much more complex programs with it, they discovered that lots of things really want to use pointer to integer conversions for things like trees and hash tables. There were some really nasty corner cases, such as hash tables that ‘worked’, but ended up putting every object in the first hash bucket, giving truly awful performance. It also introduced more subtle bugs in things that used address order for consistent lock-acquisition order. These last ones are fundamentally incompatible with copying GC and so it became clear that this was not a model for C/C++ that would be able to compile large codebases without modification.

Alex and Jess fixed that in the compiler, but the core hardware abstractions remained largely unchanged. In CHERIoT, we removed the last vestiges of offsets by removing the set-offset instruction, because the extra addition hurt critical path lengths. I still believe that this was the right thing to try for research, but it’s not research if you know it will work in advance, and this one didn’t work at all.

The other big change that was in before the paper was to generalise the sealing mechanism.

The first public version of the CHERI ISA contained two instructions for sealing, CSealCode and CSealData (pages 97 and 99).

These were intended to create cross-domain entry points.

A cross-compartment call would be represented by two capabilities sealed with the same type.

These would be installed in the PCC and an invoked-data capability register during a compartment call.

By the 2015 paper, these were replaced by a single CSeal instruction that could seal pairs of capabilities in this way but could also seal capabilities independently.

This let us implement opaque data types using sealed capabilities, something that we do extensively in CHERIoT (see this section of the CHERIoT book for a longer explanation of CHERI object types and sealing).

I think our first public use of this (it was used a lot as an aside elsewhere) was our 2017 paper that extended type safety from Java code across the JNI boundary.

The CCall instruction at the time was actually a trap (with the expectation that a future version would move some or all of the trap handler into hardware).

It branched to a handler, as did CReturn.

The software stack in the paper used these to implement a trusted stack for cross-compartment calls.

In CHERIoT, we use a very similar model but don’t need a special instruction.

We use the sealed entry (sentry) model, where one object type is reserved for capabilities that you can branch to but can’t do anything else with.

This was added a few years after the 2015 paper and meant that CHERIoT started from a model where the trap was not necessary.

Using sentries means that our cross-compartment call can just use a jump to a sentry to invoke the switcher, rather than a trap.

This is more scalable: a single system can provide multiple switchers like ours, but the 2015 paper required one per address space.

In CHERIoT we extend sentries to control interrupt state and to differentiate between forward and backwards control-flow edges.

If you look at the way that the ccall switcher works the 2015 paper, you’ll see something that is quite recognisable from the CHERIoT compartment-switch routine. Both maintain a trusted stack and use it in similar ways. The paper expects each compartment to have its own stack (which made multithreading hard. Dapeng Gao is doing exciting work here), whereas CHERIoT reuses and zeroes the stack. The CHERIoT approach is optimised for small systems. Modern microcontrollers are fast but have small amounts of memory. Stacks are small and so zeroing them is a low overhead, whereas requiring a lot more stack would put more pressure on the most scarce resource in the system.

This paper also describes the pure-capability ABI. This lowers every pointer to a CHERI capability and was possible only because the offset had been added. Back then, I was calling this the ‘sandbox ABI’ because we couldn’t use it for complete programs (Robert Watson convinced me that was a terrible name). It wasn’t until a few years later that (led by Brooks Davis but with a lot of amazing work from others) we finally had a complete CHERI userspace. If you read only one CHERI paper, the 2019 one describing that system is probably the one you should read (this one won the ASPLOS Best Paper Award). The 2024 IEEE Security & Privacy journal paper gives a better high-level overview, but the CheriABI paper and the extended technical report version provide a lot more detail in how CHERI can build a complete solution.

Some things have changed

At the same time, it would be somewhat sad if CHERI had already been perfect in 2015 and it took another decade to get anything into production. Quite a few things have changed since then. Some are big, some are small refinements.

The most disruptive to the bits of software that I worked on, which I think happened a year or two after this paper, was that the capability and integer register files were merged. The original CHERI prototypes used MIPS and used the coprocessor 2 encoding space. This made it natural to view the capability unit like a floating-point unit: something with its own register file. It turned out that this complicated ABIs, made cores bigger, and didn’t really add any benefits. Later versions merged the two. The MIPS variant maintained both options for a while.

More visibly to the rest of the software stack: Capabilities back then were 256 bits! This was great for initial prototypes. We originally had a 64-bit base, a 64-bit top, a 64-bit object type, a large space for permissions (31 bits, though most were available for software to use), and some space left over. We also had a separate sealed bit, though after a while we realised that this was just an expensive way of encoding the fact that the object type was not zero. This was great for a research prototype because there were always spare bits for experiments (though adding the offset required shrinking the object type: we made it 24 bits then, on CHERIoT it’s 3 bits and we virtualise it).

Doubling the size of pointers was a hard sell, quadrupling the size would have been impossible. It was also painful for large processors to require 256-bit data paths across the load-store unit and register file. It took a while to get it published, but the CHERI Concentrate paper describes how we shrunk this down to 128 bits, inspired by the Low-fat pointers work. The first public references to this work are in the 2015 technical report. CHERIoT had to shrink this further and had other microarchitectural constraints for short pipelines, which is why we support two capability formats for different scales of devices.

And, of course, the MIPS prototypes have been replaced with RISC-V. 64-bit big-endian MIPS was never well supported and RISC-V reached parity quite quickly and provided a better ecosystem for experimentation and technology transition.

Finally, you’ll note that the 2015 paper is silent on the topic of temporal safety. There were a lot of experiments going on for temporal safety but the first one that worked well over large codebases was Cornucopia, published in 2020. Wes Filardo (an original and continuing member of the CHERIoT team) drove a lot of this along with the 2024 Cornucopia Reloaded follow-up work to move to a load barrier. This model works on Morello and on the upcoming RISC-V 64-bit CHERI specification.

As often happens with long publication delays in academia, our 2023 CHERIoT paper includes work inspired by this. The CHERIoT temporal safety approach replaced the Cornucopia Reloaded MMU-based load barrier with a hardware load filter and built on some other ideas that came from our work to compose CHERI with Arm’s memory tagging extensions (MTE). These haven’t yet been published, but experienced microarchitects estimate that they would get the overhead of temporal safety for big superscalar CHERI implementations to under 2%.

CHERIoT adds some more things

CHERIoT started in 2019 and tried to scale the ideas down. The 2015 paper didn’t mention a 32-bit option at all. The 2018 CheriRTOS paper based on Hongyan Xia’s PhD work was, I think, the first public work to scale down to 32 bits. This had a lot of limitations from the encoding (Hongyan was one of the original CHERIoT team and we learned a lot from his experience).

CHERIoT adds more kinds of sentries, temporal safety, a richer set of permissions, and closer co-design between the hardware and software.

The original DARPA challenge asked what you would change ‘if you could change anything’. In some ways, CHERI was the least ambitious project on that programme because we cared a lot about backwards compatibility and incremental adoption. The 2015 paper makes it clear that you can simply opt out of CHERI for some processes (you don’t need to recompile the world) and that you can use legacy ABIs in sandboxes with a bit of glue code doing copying. This kind of incremental adoption story is really important, but on embedded systems incremental adoption looks quite different. Most embedded code has few dependencies from the host environment, which gave us a lot more freedom to build efficient models that scale right down to tiny devices. Many of these would be possible for green-field software on bigger devices, but you can’t build those unless CHERI is widely deployed and you can’t deploy CHERI widely without CHERI-enabled CPUs running existing software stacks.

We aren’t finished yet!

The CHERI project has been going on for 15 years now, and CHERIoT for six of those. CHERI is a bigger change than adding memory management units (MMUs) to systems. The core ideas in MMUs came from the 1970s, yet people are still coming up with new variations on MMUs and new software abstractions that use them. We are now at the state with CHERI where we were with MMUs in the 1990s: We understand some very useful things that can be built with CHERI and we are now good at building those things, but there’s still a large set of things that we haven’t considered.

I expect CHERI to enable a lot of new software patterns that will provide a much larger benefit than anything that we’ve seen so far. Fixing 70% of security vulnerabilities and providing fine-grained compartmentalisation for fearless code reuse is just the start!